Written by KJ Sakura

In early January of this year, I enjoyed a three and a half hour tour of one of my favorite sake breweries, Kenbishi. It is located in the Nada Ward near the port of Kobe in Hyogo Prefecture. Visits to the brewery are not open to the public; yet I was able to take this amazing tour with the WSET teacher candidates and liaisons from the National Tax Agency of Japan. Our host was the eloquent and humble President Masataka Shirakasi. He was our ambassador and guided us through their company principles, the history of the brand and every aspect of brewing.

He began by bringing us to the roof of the large brewery (one of 4 identical facilities). Excitement arose when spotting an enormous kodaru barrel with Kenbishi’s iconic logo which we immediately stopped in front of to take photos. Once settled in a small classroom overlooking the nearby canal, Mr. Shirakasi introduced himself as the president of the company. He mentioned that Kenbishi is the oldest brand of sake which was established in 1505. They are also the 3rd oldest brewery still active in Japan (there are two others, but they have changed brands since inception). They produce 20,000 koku yearly (equivalent to 400,000 cases of wine) and export 71 koku to the USA, Italy and France. After giving us some statistics, he introduced to us the history of the region and explained the pillars in which their company is founded.

The first and most fundamental pillar is: “Be a Still Clock. It is more important to maintain our traditions and create the confident taste that our customers appreciate. A slow clock may never tell the right time, but a stopped clock is right twice a day.”

Mr. Shirakasi expanded on this concept by adding, “Do not chase the trend. Make the trend, don’t follow. If you follow, you are already late. Don’t chase the clock. Keep tradition.” I find this metaphor intriguing and inspiring. This principle manages to encompass the idea of not following the trends, but instead making the trend and waiting for the trend to return to you once again. In that time, the company focuses their time on creating the best examples of their traditional style without wasting energy on gimmicks and fads to attract new consumers.

Secondly, “What we receive from our customers’ pockets shall be returned to their mouths” When our customers choose to pay for our sake, they are telling us to create delicious sake again. Because we value their message, we must buy high-quality rice and spend time and effort making wonderful sake.”

I like this pillar for two reasons. Although a bit clunky in English translation, the idea that the money invested in a product will pay back equally in quality and flavor is forthright and provides an automatic sense of trust. Without previously realizing it, this is the reason I always go back to Kenbishi. For its complexity, its unique flavor profile and knowing it was worth the money I spent on it. It is also fantastic that they interpret purchases not as expected revenue, but as a message from the customer that they are doing a great job. Kenbishi’s unwavering commitment to high quality products is the reason they operate with only one marketing staff member. This is very unusual for a company of this status and size.

The last family principle is, “Make an effort to set an affordable price. We must keep an affordable price for customers. High profit is superfluous because if we get it, we lose trust between our customers and us. Therefore, be faithful to the price. We don’t betray the customer’s trust.”

Shirakasi-san also mentioned, “Do not overprice. Kenbishi has been enjoyed from Emperor to local people for hundreds of years.” It is important to the company to create the best sake possible, but keep the price low enough for people of all lifestyles to access. They want their sake to be enjoyed casually on a more frequent basis versus being enjoyed only for special occasions.

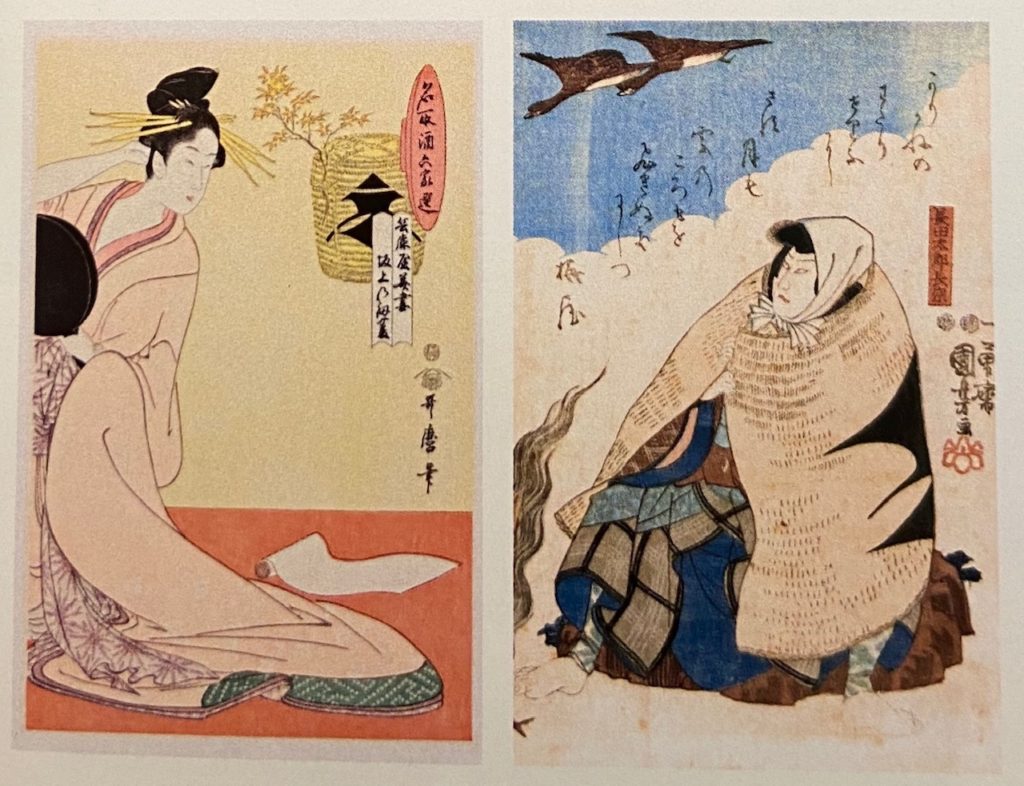

What Kenbishi lacks in advertising, it makes up for in memorable labeling. Anyone who sees a Kenbishi bottle is immediately drawn to the distinct contrasting characters in black and white. It is an artistic representation of a sword and a diamond, which relate to the harmony between a man and a woman. I have also heard that the sword itself relates to samurai who were big fans of the brewery and consumed Kenbishi on a regular basis. The famous logo was immortalized in the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō (slave version) by Utagawa Hiroshige and various other ukiyo-e woodblock prints during the Edo period. SakeTips! founder Saki Kimura made a wonderful video about the Kenbishi logo which can be viewed here: Kenbishi by Saki Kimura.

Kenbishi can also claim to exude terroir in their sake by using rice grown in the area near Mount Rokko. They contract 18 rice growers and use one fifth of the Yamada Nishiki grown in the region! They also use Aiyama, a lesser known rice variety. It was considered a great component of sake production by Shirakasi-san’s grandfather. One of the most influential ingredients representing terroir is the highly regarded Miyamizu water. The water is known to be rich in minerals, yet lacking in iron which is a detrimental element for sake production. The region doesn’t have the influence of volcanic activity, which eliminates ash issues and reduces iron in the water. The other special or “mysterious” aspect of Miyamizu was explained thoroughly by Shirakasi-san. He mentioned that when rainfall slowly travels from Mt. Rokko to the subsoil, there are meeting points with rivers in the area. The fresh river water flushes the subsoil water with oxygen, so any iron that exists will become an oxidized ion and then sink to the bottom. It’s almost like a natural filtering of iron by oxygen influence! The higher mineral content of the water without the iron allows for a more vigorous fermentation and more nutrients for the yeast.

After getting a serious lesson on all things Kenbishi, we eagerly entered the brewery. We were lucky enough to visit during brewing season, where we were greeted by the kurabito who make the magic happen. There are 90 workers but 80 of them are diving fishermen working during their off-season. They come from Ishikawa and Fukui Prefectures to make money during the winter when brewing begins (October-April). To give the workers a sense of home, the company ships fish from the Sea of Japan twice a week because the men don’t like to eat fish from the Pacific Ocean! That kind gesture is maximized by allowing them to drink Kenbishi sake to their heart’s content. They consume 3,000 bottles of 1.8L which equates to 5400L per season and approximately half a standard 720ml bottle per person nightly!

When I saw the men working in such wet conditions (such as breweries are), I thought of how genius it was to hire men who make their primary living submerged in water for hours a day. I imagined they felt this difficult, damp work was a break from their normal careers!

An intriguing part of our tour was being able to view koji production in action. They let us all inside while work was taking place. It was surprising to me since some breweries are very strict about who can be inside the kojimuro while it is being prepared. There are 4000 trays (kojibuta) in the koji room. The warmer trays are on top and colder on the bottom. They are rotated 4 times a day to keep at an even temperature and assure that koji mold grows evenly on each grain of rice. Another way to maintain even temperature is having trays with various thickness on the bottoms. The middle of the trays are thinner and the sides are thicker. It takes a total of 52 hours to make the koji starting at 28C then can reach up to 50C (82F to 122F). The room is non-heated. All warmth is provided from the koji production itself. The koji for shubo can reach 60C (140F).

They make their koji in the so-haze style which is where the koji mold (aspergillus oryzae) growth is deep inwards as well as across the surface. This type of koji is more common in savory, earthy style sake. We were allowed to taste the koji rice and it was so good! It had a fluffy texture and reminded me of a lightly sweet brie cheese rind!

The moromi (main fermentation mash) lasts 30 days with ambient yeast. They make consistent yamahai styles by allowing lactic acid to occur naturally during the shubo. They feel the “secret” to their style of sake is the length of the moromi, allowing ambient yeasts for fermentation and their flavorful so-haze koji. They have a low kasu-buai percentage of 12%, meaning that 88% percent of the mash has liquified and become drinkable sake. Every release is a blend of aged sakes which gives their products it’s quintessential umami flavor.

I assumed the tour was over when we were directed to a room with gigantic rice milling machines. It is extremely uncommon for a brewery to mill their own rice. They are also one of the breweries that is certified in grading and inspection. There are 10 inspectors at the brewery who check for dips in grain, hardness of rice and contamination. Sometimes rice growers will sneak in other rice varieties of lesser value than what was purchased. The machines were purchased 15 years ago and they sell the nuka rice powder to oil manufacturers, as well as animal food and rice cracker companies.

The next epic room contained eighteen moromi 1000L tanks. The tanks used to be made of wood but were destroyed by the great Hanshin earthquake in 1995. They were rebuilt with steel and concrete to avoid another disaster. Most of the tanks contain 1-3 year old sake with some holding sake as old as 39 years! Consistency is key which is why the blender’s job is so important. The goal is to reach “forever Kenbishi” which represents the style they are known for. They have over 300 tanks at all four locations used for blending.

The last room we visited was their crafting workshop. The brewery is committed to using time-tested tools to produce their unchanging style. Wood is used for the koshiki rice steamer to absorb excess water and prevent condensation. They wash the wood above the boiler yearly and the bamboo is changed every three years. They prefer to use wood over stainless steel because even though it is easier to clean, it is harder to keep at a stable temperature. The shubo lasts for 20-40 days and is kept at stable temperature with an old school dakidaru. The dakidaru is a sealed water bucket which has hot water from 40-60C inside. It is manually rotated in the shubo by a kurabito. One person makes 30 dakidaru per year and they last 7-8 years. They cost $1300 a piece. 99% of Kenbishi’s profits come from sake production and the other 1% is the sales of these special wooden crafts. Kenbishi has hired three craftsmen to produce these tools and steamers. They also sell them to other breweries.

Another way they utilize materials is using rice straw to make shimenawa, which is a sacred woven rope. They are wrapped around objects to attract kami spirits and good fortune. This type of rope is commonly found on sake barrels used for celebrations or ceremonies. Nowadays most examples of this rope are synthetic, but Kenbishi keeps the ancient tradition alive.

We finally made it to the end of a thoroughly engaging brewery tour and had the chance to taste through their one of a kind sakes! First was the Mizuho Junmai which I have tasted at trade shows, but have never had the pleasure of selling. It is aged for 2 to 8 years, is made from Yamada Nishiki rice and has a 17% alcohol content. Milling rate changes slightly yearly, with koji being the main factor in decision making. In general, it is around 70% remaining rice. This sake is leaner than the other two we tasted, with intense flavors of toasted caramel, miso and cocoa beans. They generously gave us each a bottle to take home!

Kuromatsu “Black Pine” Honjozo is aged for 3 to 5 years with jozo alcohol added. They mentioned that this technique began in the 17th century, with influence from Spain and Portugal (fortified wine anyone?). In theory, honjozo styles tend to be leaner due to the alcohol addition. In this case, Kuromatsu expressed itself with a richer texture and more mouthfeel than Mizuho. The texture of this sake is my favorite part! The aromas of candied nuts, molasses and dashi broth made this small taste a decadent palate experience. I have been happily selling this sake for many years, due to its unrivaled flavorful profile, its ability to pair with foods from many cuisines and its ability to be enjoyed at any temperature (my favorite is room temp). Kenbishi also makes a small 180ml bottle version which can be heated easily in the microwave. Most breweries would shun the idea of their sake being treated so indelicately, but Kenbishi embraces the custom. They have developed a way to make the experience easier for customers to enjoy.

It is hard to choose a favorite sake when they are all so extraordinary, but one in particular fully caught my attention. It is called Kenbishi Zuisho. Zuisho translates to “good omen,” which is the essence I felt while tasting this otherworldly brew. It ignited feelings and memories from many moons ago. As a beverage professional, the rare occasions when this occurs are lightbulb and eureka moments! That discovery, that connection from palate to mind can only happen when a product is given the utmost in care and attention. Zuisho is a plethora of deliciousness, exuding aromas of caramel and shoyu with a touch of buttered popcorn on the finish. The sake glides on the palate with ease, helping the drinker experience the magnificence of the beverage while strolling down memory lane. This sake is technically considered koshu with ageing between 5-15 years. This is the one product not currently exported to the USA market! If available, I would enjoy this sake every evening in lieu of dessert or coffee.

Kenbishi makes momentous, persistent and meaningful sake. They have a modern sensibility balanced by a deep rooted commitment to tradition. It is so cool that the brewery is profoundly self sustainable and a protector of time-honored sake arts. I know for sure that Kenbishi will be a still clock for another 500 years; producing sake the same way their forefathers did 1000 years prior. Imagine that!